Emigrating to Australia in 1965

In 1965 I decided to emigrate

to Australia. My decisions to leave the "Fatherland" was made as hastily and

as much on the spur of the moment as every other decision I have made before and since.

Avoiding eighteen months of military service had something to do with it. Escaping what

was shaping up to become a fairly mundane and ordinary life was another.

Two years earlier I had successfully completed my articles with an insurance company and

made my first escape of sorts: I had joined the large highway construction company Sager

& Woerner as their payroll clerk. There were three of us in the office: the two

"Schwaben" Dietl and Spoerl (always properly addressed as "Herren")

and myself, not yet eighteen years old but learning fast. Our mobile office followed every few

months the "Autobahn" under construction from Walsrode to Verden an der

Aller to Bremen. Already, although not yet articulated, "Have pen, will travel" had

become the motto of my life.

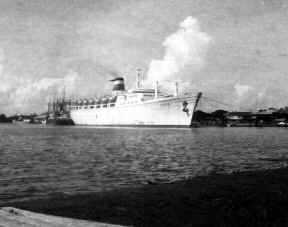

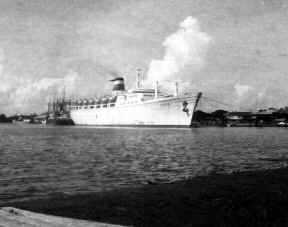

My recollection of dates is a bit hazy but it was sometime in July 1965 when I boarded the

FLAVIA in Bremerhaven. The Australian immigration department had offered me an airline

ticket to get to the other side of the world, but as I had to sell my beloved stamp

collection to raise the required £50 for the assisted passage out, I thought it only

fair that I ought to get my money's worth and take the six-week sea voyage via Tilbury,

Curaço, the Panama Canal, Papeete, and Auckland, to Australia.

My recollection of dates is a bit hazy but it was sometime in July 1965 when I boarded the

FLAVIA in Bremerhaven. The Australian immigration department had offered me an airline

ticket to get to the other side of the world, but as I had to sell my beloved stamp

collection to raise the required £50 for the assisted passage out, I thought it only

fair that I ought to get my money's worth and take the six-week sea voyage via Tilbury,

Curaço, the Panama Canal, Papeete, and Auckland, to Australia.

I was told, "If you want a pleasant voyage don't travel from Europe on a migrant ship."

I am glad I did not follow the advice. The boat

was crowded but it was good to be among people who

were good to each other because they were sharing a common adventure, the greatest they had

known. We were all looking forward to living in a country where there was space, and room

to grow, and where hard work was rewarded. There were no streamers at Bremerhaven, and no

band was playing: people stood quietly on the rain-moist deck as the last visitors were

ordered ashore. Then the slow, sonorous, terrible blast on the ship's siren; suddenly a

gap had opened between ship and land: we were on our way; there was no going back!

I was told, "If you want a pleasant voyage don't travel from Europe on a migrant ship."

I am glad I did not follow the advice. The boat

was crowded but it was good to be among people who

were good to each other because they were sharing a common adventure, the greatest they had

known. We were all looking forward to living in a country where there was space, and room

to grow, and where hard work was rewarded. There were no streamers at Bremerhaven, and no

band was playing: people stood quietly on the rain-moist deck as the last visitors were

ordered ashore. Then the slow, sonorous, terrible blast on the ship's siren; suddenly a

gap had opened between ship and land: we were on our way; there was no going back!

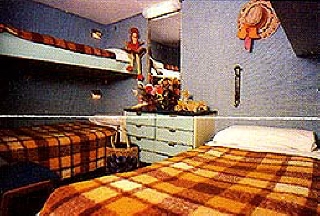

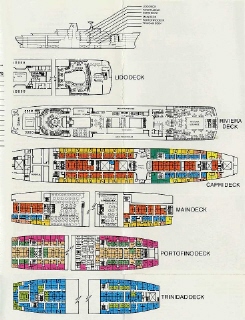

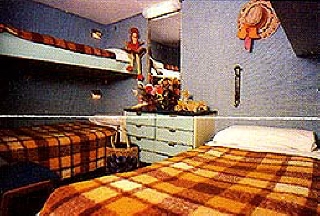

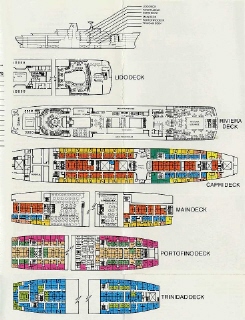

In the bowels of the ship order emerged from disorder. We were accommodated in 6-berth cabins

on the lowest deck, Trinidad Deck, with no portholes and shared facilities.

As we headed south and out into the Atlantic. the warming sun spread animation among the

passengers now settled into a daily routine, punctured by ample meals.

In the bowels of the ship order emerged from disorder. We were accommodated in 6-berth cabins

on the lowest deck, Trinidad Deck, with no portholes and shared facilities.

As we headed south and out into the Atlantic. the warming sun spread animation among the

passengers now settled into a daily routine, punctured by ample meals.

English classes

got under way properly where we were asked to form a credible "th" sound and to

differentiate the "v" from the "w". Learning English was no game for us: our

future depended on it. The shipboard cinema showed Australian documentary films which we

watched with intense concentration.

There were the usual shipboard diversions: deck games and

the pool (always too crowded and always too low on water) during the day and music and dances

and fancy dress balls and bingo in the evenings but overarching all these activities was the

one question that was on all our minds: what would await us in Australia? We used to sit up

in our six-berth cabin long into the night worrying and wondering about it.

English classes

got under way properly where we were asked to form a credible "th" sound and to

differentiate the "v" from the "w". Learning English was no game for us: our

future depended on it. The shipboard cinema showed Australian documentary films which we

watched with intense concentration.

There were the usual shipboard diversions: deck games and

the pool (always too crowded and always too low on water) during the day and music and dances

and fancy dress balls and bingo in the evenings but overarching all these activities was the

one question that was on all our minds: what would await us in Australia? We used to sit up

in our six-berth cabin long into the night worrying and wondering about it.

I will always

remember one of my cabin-mates, a young butcher from Berlin, who was constantly

dressed in a fishnet-shirt (to solve his laundry problem, as he put it, and which left an

interesting tanning pattern on his upper torso).

Nothing seemed to bother him much; not our uncertain future nor the English lessons which he

had dispensed with in favour of the bar. As far as he was concerned, if things didn't work out

he could always commit suicide! An interesting outlook on life, to say the least, and the solving of one's

problems. I have sometimes wondered how he ended up?

I will always

remember one of my cabin-mates, a young butcher from Berlin, who was constantly

dressed in a fishnet-shirt (to solve his laundry problem, as he put it, and which left an

interesting tanning pattern on his upper torso).

Nothing seemed to bother him much; not our uncertain future nor the English lessons which he

had dispensed with in favour of the bar. As far as he was concerned, if things didn't work out

he could always commit suicide! An interesting outlook on life, to say the least, and the solving of one's

problems. I have sometimes wondered how he ended up?

Both then and now, the whole voyage has been a bit of a blurr: we passed through the Panama Canal,

and made a brief refuelling stop at Papeete,

Both then and now, the whole voyage has been a bit of a blurr: we passed through the Panama Canal,

and made a brief refuelling stop at Papeete,

after which we headed towards Auckland, New

Zealand. With no money in my pockets and so much at stake, this was no pleasure trip!

Sometime during the voyage and under circumstances which I have long forgotten,

I had made friends with a young German who had come out to Australia many years before with his parents

as a child. He was now married and on his way back from a trip to Europe with his wife, baby,

and mother-in-law with whom he had revisited his own hometown and that of his Yugoslav wife.

This friendship was going to have a major impact on my future life in Australia

(of which I shall tell more momentarily), and to this day Hans and I have remained good friends.

after which we headed towards Auckland, New

Zealand. With no money in my pockets and so much at stake, this was no pleasure trip!

Sometime during the voyage and under circumstances which I have long forgotten,

I had made friends with a young German who had come out to Australia many years before with his parents

as a child. He was now married and on his way back from a trip to Europe with his wife, baby,

and mother-in-law with whom he had revisited his own hometown and that of his Yugoslav wife.

This friendship was going to have a major impact on my future life in Australia

(of which I shall tell more momentarily), and to this day Hans and I have remained good friends.

Soon, but to us not soon enough, the outline of the Australian coast and of the city of Sydney

hove into sight. There they were, those famous golden beaches of which had spoken the brochures

that the immigration department had given us. Here many passengers left us, as did Hans who was

heading for his hometown Canberra, but for us, the migrants, the "New Australians"

as we were henceforth to be known, the voyage continued to the port of Melbourne.

We disembarked in some sort of organised chaos at Port Melbourne and soon afterwards

boarded a train for the inland town of Albury from where we were taken to the

Migrant Centre at

Bonegilla. Remember the movie "The Great Escape"? Well, Bonegilla was a camp

along the lines of what you saw in that movie - except that Bonegilla was a darn sight worse.

We were put into corrugated-iron huts in what had been an old Army Camp - and I believe

the old Spartans enjoyed more comforts than did the inmates of the "Bonegilla Migrant Centre".

Although we were in the depth of the Australian winter (which can be pretty cold in the

Australian inland), there was no more than a one-bar electric strip heater on the wall

above the bed and a fairly threadbare ex-Army blanket to ward off the cold at night.

For somebody who had just avoided conscription into the German "Bundeswehr",

it seemed a poor exchange.

We disembarked in some sort of organised chaos at Port Melbourne and soon afterwards

boarded a train for the inland town of Albury from where we were taken to the

Migrant Centre at

Bonegilla. Remember the movie "The Great Escape"? Well, Bonegilla was a camp

along the lines of what you saw in that movie - except that Bonegilla was a darn sight worse.

We were put into corrugated-iron huts in what had been an old Army Camp - and I believe

the old Spartans enjoyed more comforts than did the inmates of the "Bonegilla Migrant Centre".

Although we were in the depth of the Australian winter (which can be pretty cold in the

Australian inland), there was no more than a one-bar electric strip heater on the wall

above the bed and a fairly threadbare ex-Army blanket to ward off the cold at night.

For somebody who had just avoided conscription into the German "Bundeswehr",

it seemed a poor exchange.

Deep blue skies and brilliant sunshine during the day made up for the freezing nights.

It was only a day or two after I had arrived in camp and while I was "thawing"

out in the midday sun when another German who had come off the ship with me, told me

about a "German Lady" at the camp's reception centre who was offering to take three or four

recently arrived German migrants back to Melbourne to board at her house. I had been

"processed" by the camp's administration on the first day and knew that in all likelihood

I was destined to be sent to Sydney to work as labourer for the Sydney Water Board. So what

did I have to lose? In record time I had myself signed out by the "Camp Commandant",

my few things packed, and was sitting, with three other former ship-mates, in a VW Beetle

enroute back to Melbourne.

Deep blue skies and brilliant sunshine during the day made up for the freezing nights.

It was only a day or two after I had arrived in camp and while I was "thawing"

out in the midday sun when another German who had come off the ship with me, told me

about a "German Lady" at the camp's reception centre who was offering to take three or four

recently arrived German migrants back to Melbourne to board at her house. I had been

"processed" by the camp's administration on the first day and knew that in all likelihood

I was destined to be sent to Sydney to work as labourer for the Sydney Water Board. So what

did I have to lose? In record time I had myself signed out by the "Camp Commandant",

my few things packed, and was sitting, with three other former ship-mates, in a VW Beetle

enroute back to Melbourne.

The "German Lady" had turned out to be a very enterprising roly-poly German

housewife who with her German husband, a bricklayer, operated something of a

boarding-house from their quaint little place in West Brunswick in Melbourne. The place

seemed already full to overflowing with young Germans from a previous intake, with bodies

occupying the lounge-room sofa, a make-shift annex, and an egg-shaped plywood caravan in

the backyard. My ship-mates joined that happy crowd but I was "farmed out" to

a nice English lady across the road who had a spare room.

The very next day the "German Lady" took me to the local Labour Exchange and

in seemingly no time had secured me a job as 'Trainee Manager' with Coles & Company

which had foodstores all over Melbourne. There I was, refilling shelves with groceries

and helping blue-rinsed ladies take their shopping to the car. I still joined the

others for breakfast and dinner in the "German house"and also had my laundry

looked after by the "German Lady" but I was already making my own way

in Australia. Looking back, my life seems to have been full of such serendipitous

encounters because more good luck was to follow!

During the first days in Melbourne I had written to Hans in Canberra to let him know

where I was, and before long he was on the 'phone to me suggesting

that I might want to come up to Canberra. I didn't need much

persuading! Hans got me a job as storeman/driver in the hardware & plumbing supplies

company of Ingram & Sons in Canberra's industrial suburb of Fyshwick. I drove an

INTERNATIONAL truck and delivered anything from ceramic floor tiles to bathtubs and

roofing iron to building sites all over Canberra. Not that I had a driver's license

for a truck or had ever driven a truck before in my life but this was Australia, a young

and vigorous country still largely devoid of formalities, and an even younger city, Canberra,

still in the making: Hans simply took me down to the local Police Station where everybody

seemed very impressed with my elaborate German "Führerschein" and where I

was promptly issued with a much simpler but oh so much more useful Australian driving license.

I kept at this job for a few months but after I had almost burnt out the truck's diff at Deakin High

School while bogged down in the mud with a full load on the back, and a slight but still embarrassing

collision with the rear-end of another vehicle just outside the British High Commission, I

thought it best to cash in my chips while I was still ahead. I had earlier on answered an

advertisement by the Australia & New Zealand Bank for school-leavers to join their ranks

and, to my own surprise and joy, was accepted. I joined the ANZ Bank and, well,

as the saying goes, the rest is history (... and what a

history it has been!).

My recollection of dates is a bit hazy but it was sometime in July 1965 when I boarded the

FLAVIA in Bremerhaven. The Australian immigration department had offered me an airline

ticket to get to the other side of the world, but as I had to sell my beloved stamp

collection to raise the required £50 for the assisted passage out, I thought it only

fair that I ought to get my money's worth and take the six-week sea voyage via Tilbury,

Curaço, the Panama Canal, Papeete, and Auckland, to Australia.

My recollection of dates is a bit hazy but it was sometime in July 1965 when I boarded the

FLAVIA in Bremerhaven. The Australian immigration department had offered me an airline

ticket to get to the other side of the world, but as I had to sell my beloved stamp

collection to raise the required £50 for the assisted passage out, I thought it only

fair that I ought to get my money's worth and take the six-week sea voyage via Tilbury,

Curaço, the Panama Canal, Papeete, and Auckland, to Australia.

I was told, "If you want a pleasant voyage don't travel from Europe on a migrant ship."

I am glad I did not follow the advice. The boat

was crowded but it was good to be among people who

were good to each other because they were sharing a common adventure, the greatest they had

known. We were all looking forward to living in a country where there was space, and room

to grow, and where hard work was rewarded. There were no streamers at Bremerhaven, and no

band was playing: people stood quietly on the rain-moist deck as the last visitors were

ordered ashore. Then the slow, sonorous, terrible blast on the ship's siren; suddenly a

gap had opened between ship and land: we were on our way; there was no going back!

I was told, "If you want a pleasant voyage don't travel from Europe on a migrant ship."

I am glad I did not follow the advice. The boat

was crowded but it was good to be among people who

were good to each other because they were sharing a common adventure, the greatest they had

known. We were all looking forward to living in a country where there was space, and room

to grow, and where hard work was rewarded. There were no streamers at Bremerhaven, and no

band was playing: people stood quietly on the rain-moist deck as the last visitors were

ordered ashore. Then the slow, sonorous, terrible blast on the ship's siren; suddenly a

gap had opened between ship and land: we were on our way; there was no going back!

In the bowels of the ship order emerged from disorder. We were accommodated in 6-berth cabins

on the lowest deck, Trinidad Deck, with no portholes and shared facilities.

As we headed south and out into the Atlantic. the warming sun spread animation among the

passengers now settled into a daily routine, punctured by ample meals.

In the bowels of the ship order emerged from disorder. We were accommodated in 6-berth cabins

on the lowest deck, Trinidad Deck, with no portholes and shared facilities.

As we headed south and out into the Atlantic. the warming sun spread animation among the

passengers now settled into a daily routine, punctured by ample meals.

English classes

got under way properly where we were asked to form a credible "th" sound and to

differentiate the "v" from the "w". Learning English was no game for us: our

future depended on it. The shipboard cinema showed Australian documentary films which we

watched with intense concentration.

There were the usual shipboard diversions: deck games and

the pool (always too crowded and always too low on water) during the day and music and dances

and fancy dress balls and bingo in the evenings but overarching all these activities was the

one question that was on all our minds: what would await us in Australia? We used to sit up

in our six-berth cabin long into the night worrying and wondering about it.

English classes

got under way properly where we were asked to form a credible "th" sound and to

differentiate the "v" from the "w". Learning English was no game for us: our

future depended on it. The shipboard cinema showed Australian documentary films which we

watched with intense concentration.

There were the usual shipboard diversions: deck games and

the pool (always too crowded and always too low on water) during the day and music and dances

and fancy dress balls and bingo in the evenings but overarching all these activities was the

one question that was on all our minds: what would await us in Australia? We used to sit up

in our six-berth cabin long into the night worrying and wondering about it.

I will always

remember one of my cabin-mates, a young butcher from Berlin, who was constantly

dressed in a fishnet-shirt (to solve his laundry problem, as he put it, and which left an

interesting tanning pattern on his upper torso).

Nothing seemed to bother him much; not our uncertain future nor the English lessons which he

had dispensed with in favour of the bar. As far as he was concerned, if things didn't work out

he could always commit suicide! An interesting outlook on life, to say the least, and the solving of one's

problems. I have sometimes wondered how he ended up?

I will always

remember one of my cabin-mates, a young butcher from Berlin, who was constantly

dressed in a fishnet-shirt (to solve his laundry problem, as he put it, and which left an

interesting tanning pattern on his upper torso).

Nothing seemed to bother him much; not our uncertain future nor the English lessons which he

had dispensed with in favour of the bar. As far as he was concerned, if things didn't work out

he could always commit suicide! An interesting outlook on life, to say the least, and the solving of one's

problems. I have sometimes wondered how he ended up?

Both then and now, the whole voyage has been a bit of a blurr: we passed through the Panama Canal,

and made a brief refuelling stop at Papeete,

Both then and now, the whole voyage has been a bit of a blurr: we passed through the Panama Canal,

and made a brief refuelling stop at Papeete,

after which we headed towards Auckland, New

Zealand. With no money in my pockets and so much at stake, this was no pleasure trip!

Sometime during the voyage and under circumstances which I have long forgotten,

I had made friends with a young German who had come out to Australia many years before with his parents

as a child. He was now married and on his way back from a trip to Europe with his wife, baby,

and mother-in-law with whom he had revisited his own hometown and that of his Yugoslav wife.

This friendship was going to have a major impact on my future life in Australia

(of which I shall tell more momentarily), and to this day Hans and I have remained good friends.

after which we headed towards Auckland, New

Zealand. With no money in my pockets and so much at stake, this was no pleasure trip!

Sometime during the voyage and under circumstances which I have long forgotten,

I had made friends with a young German who had come out to Australia many years before with his parents

as a child. He was now married and on his way back from a trip to Europe with his wife, baby,

and mother-in-law with whom he had revisited his own hometown and that of his Yugoslav wife.

This friendship was going to have a major impact on my future life in Australia

(of which I shall tell more momentarily), and to this day Hans and I have remained good friends.

We disembarked in some sort of organised chaos at Port Melbourne and soon afterwards

boarded a train for the inland town of Albury from where we were taken to the

We disembarked in some sort of organised chaos at Port Melbourne and soon afterwards

boarded a train for the inland town of Albury from where we were taken to the

Deep blue skies and brilliant sunshine during the day made up for the freezing nights.

It was only a day or two after I had arrived in camp and while I was "thawing"

out in the midday sun when another German who had come off the ship with me, told me

about a "German Lady" at the camp's reception centre who was offering to take three or four

recently arrived German migrants back to Melbourne to board at her house. I had been

"processed" by the camp's administration on the first day and knew that in all likelihood

I was destined to be sent to Sydney to work as labourer for the Sydney Water Board. So what

did I have to lose? In record time I had myself signed out by the "Camp Commandant",

my few things packed, and was sitting, with three other former ship-mates, in a VW Beetle

enroute back to Melbourne.

Deep blue skies and brilliant sunshine during the day made up for the freezing nights.

It was only a day or two after I had arrived in camp and while I was "thawing"

out in the midday sun when another German who had come off the ship with me, told me

about a "German Lady" at the camp's reception centre who was offering to take three or four

recently arrived German migrants back to Melbourne to board at her house. I had been

"processed" by the camp's administration on the first day and knew that in all likelihood

I was destined to be sent to Sydney to work as labourer for the Sydney Water Board. So what

did I have to lose? In record time I had myself signed out by the "Camp Commandant",

my few things packed, and was sitting, with three other former ship-mates, in a VW Beetle

enroute back to Melbourne.